Тщательное картографирование остатков трех нацистских лагерей времен Второй мировой войны и обнаружение еще одного лагеря для советских военнопленных — таков результат короткой экспедиции в город Карвину, которую мы предприняли в начале мая 2021 года. Толчком к этой экспедиции послужила встреча с писательницей Карин Ледницкой, которая недавно обратила внимание общественности на незаконную вырубку деревьев и разрушение остатков зданий на месте бывшего лагеря для итальянских военнопленных. Благодаря роману "Косая церковь" Карин Ледницкой удалось привлечь внимание к теме лагерей в Карвине (и не только там) — наше внимание в том числе. Именно Карин стала нашим гидом во время экспедиции. По ее итогам был создан этот короткометражный документальный фильм "Экспедиция Карвина".

Еще одной причиной, почему мы отправились в эту экспедицию, стал факт, что из-за коронавируса и невозможности выезда за границу мы были вынуждены на неопределенное время отложить экспедиции по местам ГУЛАГов на территории бывшего СССР, давно запланированные нами. Однако в чем-то это помогло нам: нельзя забывать о том, что и на нашей территории есть много мест, связанных с темным прошлым тоталитарных режимов, и их необходимо изучать.

Продолжение репортажа доступно на английском языке.

Labour camps in Karviná

In the period of World War II, Těšín Silesia was annexed by Nazi Germany and thanks to its coal reserves it became one of the most important industrial centres of the Third Reich. Tens of thousands of prisoners and POWs were forced to work there. In total, around 60 labour camps were established on the territory of today’s Czech Silesia; the four most populous were located on the former territory of Karviná. (After the town was evacuated and demolished to facilitate coal mining, Karviná and its inhabitants were “relocated” a few kilometres away to where the town of Fryštát used to be. The original site is now called “Karviná – Doly” [Karviná – Mines] and it’s a no man’s land, undermined, with some scattered buildings.) It was these four camps that we decided to visit.

After WWII, these camps and their existence were forgotten for many years, also because old Karviná was gradually abandoned and the whole area became derelict, which resulted in a gradual loss of landscape memory. Almost no documents mentioning the camps have been preserved in the Karviná archive. It was the former prisoners who drew attention to the camps – in 2012, Italian Paolo Complojero wished to visit the place of his former internment. The camp for Italian POWs was discovered by students of the Pavel Tigrid Grammar School in Ostrava who were helped by Richard Kozieł, an eyewitness from Kraviná. Consequently, employees of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum who were looking for a Jewish camp in Karviná that was mentioned by some survivors got in touch. In this way, the existence of these labour camps was rediscovered. You can find more in the article by Marcel Mahdal Discovery of a Jewish Camp in Karviná (in Czech) on the Moderní dějiny portal and in Alfons Adam’s Labour Force for Rent (in Czech) in the Paměť a dějiny journal. Two of the four camps in Karviná are also mentioned by Jiří Padevět in his book Za dráty. Tábory v období 1938-1945 na území dnešní České republiky (Behind the Wire. Camps in today’s Czech Republic in 1938–1945). We have used some factographical data from these articles in our research.

Three of the four camps (the Jewish camp and the two Soviet camps) are now on land that belongs to Asental owned by Zdeněk Bakala and to Veolia Energie ČR. Veolia had a small monument erected near the former Soviet and Jewish camp near the heating plant (where a warehouse stands now). The second camp for Soviet POWs near the Jan-Karel mine (later the ČSA mine) is not commemorated in any way; its exact location had not been known until we researched the area. The remains of the Italian camp (which was later used as a camp for expelled Germans and as a technical auxiliary battalion camp) is on land owned by Mastergame Nova, and this is where most interventions are happening right now. Not only is it not officially commemorated, but illegal logging and terrain alterations are destroying what little that has remained of this camp.

The research and documentation of the individual camps is divided into the following chapters:

1. Soviet camp near the Jan-Karel mine

2. Labour camp for Polish Jews near the heating plant

3. Soviet camp near the Barbora mine

4. Camp for Italian POWs

Our field research was carried out on 4–5 May 2021. The Gulag.cz team consisted of Štěpán Černoušek (Gulag.cz Chairman), Tomáš Polenský, Igor Suvorov, Jindřich Plzák and Lukáš Holata.. Our aim was to find the exact location of the four camps in Karviná, evaluate and describe their state of preservation, document the remains of the barracks and to catch the current state of the camps on photographs, panoramic views, drone footage and in a short documentary. We believe that our work will contribute to the preservation and protection of these places of memory that have been forgotten for many years.

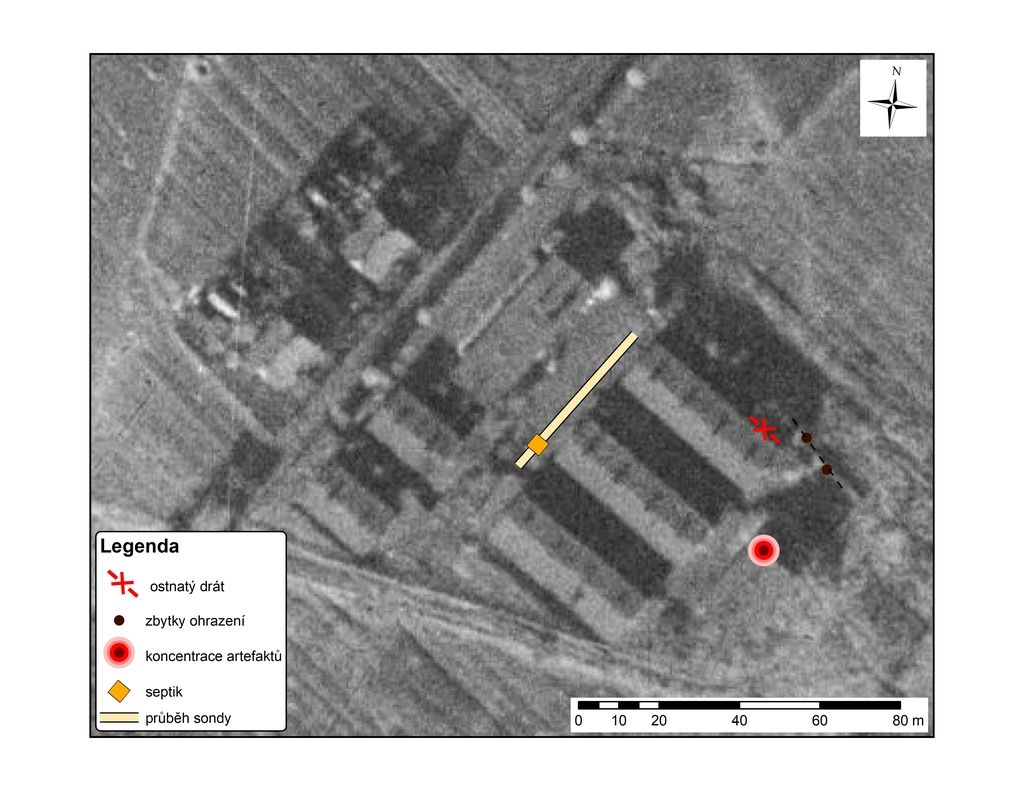

In the field, we have carried out so-called non-destructive archaeological research, which means we identified the remains of the camps by their relief traces – typically destructions and relief shapes, and to a limited extent also artefacts visible on the surface. We used GPS and documents that we have prepared – orthophotographs with coordinates (with a sufficiently dense network of the x and y coordinates) to navigate ourselves in the terrain. This method not only led us to the perimeter of the former camps, but we were also able to walk through all the places where prison barracks and other buildings used to be. During this time, we also conducted field observations in order to record any evidence that might have any connection to the camps. At the same time, we identified the best places for taking 360° panoramic photographs.

Archaeological research

Field research follows after literature search. In this case, we found orthophotographs, mainly from the years 1947–1954, in which the camps are clearly detectable – mainly the regular plan of same-sized buildings, which is typical for prison barracks. Using a geography information system we got the exact coordinates of the individual camps, which helped us find their location. People who don’t know this place and the landscape might be surprised by this procedure and by the fact that the sites of some of the camps have not been identified, not even by the eyewitnesses. This is due to the fact that the whole area is undermined, it was completely evacuated and often also systematically destroyed. This means that compared to 70 years ago, everything has changed, including the terrain with many sinkholes, which has completely transformed the landscape.

We used a total station for a more detailed mapping of the camp relics. Unlike GPS, it measures with an accuracy of a few millimetres. Unfortunately, due to the extensive transformation of the landscape, trigonometric network of points cannot be used there. Therefore, our measurements are relative, with a bigger error, but still within a limit for us to be able to compare specific terrain relics with objects on historical aerial photographs.

1. Soviet camp near the Jan-Karel mine

2. Labour camp for Polish Jews near the heating plant

3. Soviet camp near the Barbora mine

4. Camp for Italian POWs